History of the Northern Blues

A rich and continuous history.

Indigenous tribes and bands have lived with and cared for the lands of the Northern Blue Mountains—spanning Northeast Oregon and Southeast Washington—since time immemorial. Their deep knowledge, cultural traditions, and spiritual connection continue to shape the health and identity of these landscapes today.

We acknowledge and honor the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, the Nez Perce Tribe, and the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, whose enduring stewardship and relationship with these lands guide ongoing efforts to understand, restore, and sustain them.

Our Ecological Past

The Northern Blue Mountains ecoregion is a diverse area extending from northeastern Oregon into parts of southeastern Washington. Ecosystems in this region were historically shaped by fire, ignited by both lightning and Tribes. Fire maintained the landscape in a mosaic of forest types and conditions, depending on how recently (and at what intensity) it had burned. This patchy landscape reduced the likelihood of fires growing to very large sizes.

For more information on how fire shaped the Blue Mountains, check out OSU Extension Service’s Not All Flame’s the Same.

The past 100+ years of effective fire suppression, coupled with past management and grazing practices, have changed our forests - they are too dense and they have more uniform structure as seen in the Osbourne Panoramas to the right. In addition, forests have more shade-tolerant trees, like grand fir, that serve as ladder fuels, allowing fires to climb into tree canopies. These conditions make our forests more susceptible to large, intense, wildfires.

This problem is aggravated (made worse) by changing weather conditions - our fire seasons are getting longer and we experience hotter temperatures in the summers. Fire managers are finding it increasingly challenging to suppress wildfires under these conditions, leading to the current trend toward large, destructive fires.

A panoramic view of a treated forest favoring larger, fire resilient species on the left and an untreated, overcrowded forest on the right.

Partners in our Northern Blues landscape use a mix of restoration techniques to mimic the region's historical fires, make our forests more resilient to large-scale disturbances, like wildfires, insects and disease, and facilitate historic ecosystem processes. The goal of restoration is to enable healthy processes, rather than to create a specific forest structure. Restoration is an ongoing effort, rather than a “one and done” activity.

Restoration doesn’t eliminate wildfires - in fact one of its goals is to restore ecosystems’ historic fire regimes - but it does reduce the risk of large, intense wildfire, thereby protecting our forest resources, homes, recreation sites, water and air quality, and other values.

Our Human History

Like the resilience of our forests, the Northern Blue’s social and economic health also depends on the condition, function and benefits arising from its land. The unique private, public, and Tribal socio-economic history motivates our communities to work together and collaborate to find common solutions to landscape-scale problems.

Tribal History

The Northern Blues region includes the historical homelands for three federally-recognized Tribes: the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, and the Nez Perce Tribe. Since time immemorial, indigenous peoples have been stewarding this land and using it as a gathering place, a practice that continues on today.

For more information on the Tribal history of the Northern Blues, please visit the websites below.

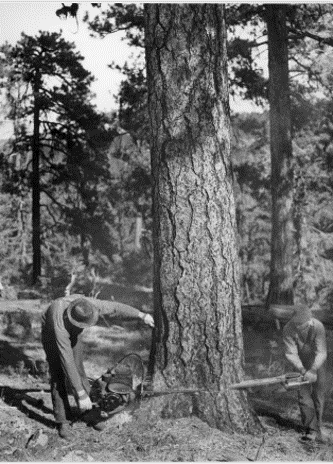

Photo credit: United States Forest Service

Timber and Wood Products

Since the early settlement of the Northern Blues, people have depended on the available natural resources to make a living. For more than a century, the forests of the Northern Blues have provided timber and other products to meet both local and national needs. Until recently, the wood products industry was a central pillar of the region’s economy. In the 1980s, annual harvests reached nearly 700 million board feet, but tighter restrictions and shifts in mill technology drove production down to less than 70 million board feet in recent years. In 1968, 65 mills operated across the region; today only five remain.

As sawmills closed, forest contractors and their equipment disappeared as well, dealing a heavy blow to areas where forest products once represented the largest source of private-sector payroll. Unemployment rates in many communities climbed to among the highest in the state, and the effects rippled outward—eroding the stability of small businesses, schools, health care services, real estate markets, and civic organizations that depended on a thriving population. These challenges were compounded by declining U.S. Forest Service staffing and investment, which had long provided steady employment and essential forest management capacity on public lands. Although all three National Forests in the Northern Blues have worked to retain resource and planning staff, reductions in capacity and investment have limited their ability to manage forests and infrastructure.

Over the past decade, timber harvests from national forest lands have varied significantly across counties. In addition to timber, many contractors now include fire suppression and service contracts with the Forest Service in their scope of work. With increased federal and state investment in forest restoration, service contracting in some counties now generates more economic value and jobs than timber harvest itself.

Ranching and Grazing

Livestock grazing has shaped the Northern Blues landscape since the 1860s, when settlers first brought cattle and sheep into the region. By the early 1900s, heavy grazing pressure contributed to reduced fire frequency, altering natural ecological processes.

Since the 1990s, grazing levels have declined due to changes in utilization standards and the resolution of resource conflicts, yet ranching continues to play a vital role in the local community, culture, and economy. Grazing on public lands—especially on national forest rangelands—remains an integral part of ranch operations, providing essential forage that supports livestock production across the region. In addition, fees collected from grazing permits contribute to county receipts and are reinvested into range improvements, helping sustain both the working landscapes and the rural economies that depend on them.

Agriculture

Agriculture in Northeast Oregon and Southeast Washington evolved remarkably over the past two centuries. With the arrival of fur traders, missionary‐settlers and emigrants following the Oregon Trail in the mid-1800s, wheat, along with cattle and sheep ranching, began to take hold.

As railroads and dry-land farming techniques expanded in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the region became part of the great Pacific Northwest wheat belt. Meanwhile in Northeast Oregon counties like Umatilla, the growth of railroads by 1897 helped the county produce nearly half of Oregon’s wheat crop. (Oregon History Project) Over time, irrigation, mechanization and diversification (including legumes, hay, and livestock) further shaped agriculture in the region — transforming it from frontier subsistence and grazing lands to a modern mixed‐farm economy rooted in dry‐land grain and livestock production.

Recreation and Services

The Northern Blues offer year-round recreational opportunities that draw both residents and visitors, from hiking, hunting, and fishing to rafting, horseback riding, and winter sports. The region is home to some of the state’s finest big game hunting, attracting tourists throughout the year and contributing significantly to local economies.

In recent years, outdoor recreation use has surged—particularly during and after COVID—bringing new opportunities but also challenges. The popularity of vacation rentals has driven up median home prices and worsened workforce housing shortages across the area.

Beyond recreation, the region’s forests provide a wide array of goods and services that support both local communities and broader society. Commercial uses include timber for sawmills, fuel, livestock forage, irrigation and drinking water, minerals, and energy. Non-timber forest products such as firewood, Christmas trees, poles, plants, herbs, traditional cultural materials, and mushrooms remain vital as well.

Equally important are the ecological services the forests provide—clean water, natural water storage, and habitat that sustains biodiversity. These benefits are closely tied to forest management and its interdependencies with local industries, infrastructure, employment, and workforce development. Ultimately, the resilience of the region—social, economic, and ecological—depends on the health and function of its public, private, and Tribal lands, underscoring the importance of sustaining both the ecological integrity of the forests and the vitality of surrounding communities.

The Northern Blues Restoration Partnership is working together to make our forests and communities more resilient.

Learn more about the history, partners, and strategies of the Partnership.